Persons of colour were mentioned regularly in the Regency newspapers. If abroad, they were slaves in revolt or in need of liberation; in Britain they were the menservants of plantation owners, dockers, or under-employed sailors in the Royal Navy or the merchant marine. They were not people whose voice was usually listened to in political debate; if they were heard, then they were saying things that the British establishment were ready to hear. Robert Wedderburn was probably the first man of colour to say what he wanted without caring what the British establishment thought of him.

Wedderburn was present at a packed meeting of the reforming establishment on August 21, 1817 at the City of London Tavern. Many of the” big names” were there; Robert Owen, currently on a tour to promote his own radical view of rural cooperative communities; Terence ( “TJ”) Wooler –journalist, publisher, republican and proto-feminist; William Hone, radical bookseller; “Major” John Cartwright, who had been making speeches about Parliamentary reform since 1780. Others such a Colonel Robert Torrens was a Malthusian and early proponent of free trade and no friend of Owen or the others; but it did not matter. There was going to be a pleasant debate. The audience was mixed; what they had in common was a belief that the present status quo in Regency Britain was unacceptable.

Owen spoke first, and for a long time. The star speaker arrived to great applause; he was about to talk about the “remoralising of the poor”. Today,” remoralising” is not even a word, but in 1817 austerity and hunger were so bad that it was felt that the poor were being demoralised and now the alternative process needed to begin. A chair was suggested and then elected. It was bureaucratic meeting Owen made his opening remarks; he was sorry that the last meeting had ended in confusion. He bemoaned the fact that not enough people there had any knowledge of political economy- what today we would call economics.

He went on the give the crowd and economics lesson that they already knew about and agreed with. Government expenditure had fallen since the end of the war; production had followed employment into a downward spiral and the “working classes” were miserable- this may have been one of the first time the expression had been used instead of the “lower orders”. Owen had a radical plan of small communities of villages that worked in co-operation. It bore no relation to any form of society that existed; it did not even include Christianity; Owen could see no connection between the practice and theory of Christianity and a society that helped each other. Owen’s utter scorn of organised religion began to alienate elements of the audience. In any case nothing was actually going to happen today; Owen merely called for a committee to consider the merits of his plan.

There then followed a procedural wrangle about previous resolutions at other meetings, whether they could be discussed if they had not been seconded, and other items of no interest to normal people either now, or then. Colonel Torrens then spoke. Robert Torrens was a Malthusian who believed that the population was rising much faster than the ability to provide food and that disaster in the form of famine or fights over resources was much more likely than Owen’s utopian communities. He proposed that Mr Owen had not adequately proved his point and suggested an adjournment of the meeting until the third Friday in January of next year.

At this point Robert Wedderburn made his contribution, after first “begging” the meeting for a mere 10 minutes to speak and at the end apologising many times for talking up their times. We know that Wedderburn made two points. That Mr Owen’s plan was another form of slavery, and he (Wedderburn) knew about slavery and that the Irish Catholic peasant was treated appallingly.

So said the establishment Morning Post, anyway.

Other papers reported it differently. The Suffolk Chronicle reported that the man the Robert Wedderburn who had made his comment about slavery was a “man of colour”. In a Regency newspaper, this word was a warning- some bad news was coming- a murder, a robbery, a revolt or a riot.

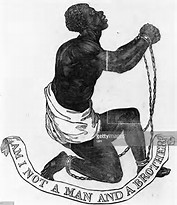

Wedderburn had clearly been trying to make his point for a long time and seemed to have forced his way onto the podium. This was breaking all the rules . A black man who asked – more demanded- to speak was somebody who scared the ladies. His inability to take a desiccated view of poverty and slavery meant that he was judged insane. He was a man of great anger and emotion, because unlike Owen, Torrens and the rest, he had felt poverty and injustice, not just though deeply about it.

So, in order to get rid of him- in effect to humour him- he was allowed to speak. He was Robert Wedderburn, some of James Wedderburn and slave women called Rosanna. That would have made him, in the ugly language of the day, a “mulato” (“little mule” in Spanish).

That’s all that we know he said. His later writings express the horror of slavery and the unique tragedy of his own situation. His father had, after his birth, sold his mother back into slavery. He may not have said that he was a Unitarian minister who denied the Trinity; a republican and a revolutionary supporter of the Spencean Philanthropists who wanted to overthrow the government. In any case, being a “man of colour ” was enough. Who did he think he was, coming into a meeting, voicing his opinions on injustice, based on real knowledge of injustice?

A cartoon of Wedderburn in action at the meeting, suggesting a degree of importance not hinted at in the newspapers. Is his stance a little like this one below, without the physical chains?

My thanks to

eblog.wordpress.com/2016/08/21/today-in-londons-radical-history-black-revolutionary-robert-wedderburn-disputes-with-utopian-socialist-robert-owen-maybe-1817/

There is more about Wedderburn’s later career in my book, Dark Days of Georgian Britain

If you are interested in the English Civil War; try these

My unusual biography of Oliver Cromwell

My ‘Fact and Fiction’ approach to the English Civil War

A study of all 59 men who signed the death warrant of Charles I in 1649

A Social History of Transport and Hospitality 1780 to 1840

A History of the Victorian Radical Movement

The Georgian Age 1720 -1820 in the words of people who witnessed it