Criminals sentenced to death by the bloody code of Regency Britain still had a soul; indeed as the rope was put around their neck, their heads covered and their hands pinioned, the hope of immortality was all they had left, so it was absolutely vital that they died well.

Charlotte Newman, aged about 30, died well. She was at Newgate, a place that excelled in the full ritual of execution. She was found guilty of a crime against property- forging banknotes. If she had starved her child to death, she would have had suffered two years in prison. Creating and passing fake notes was easy, too tempting for the poor and led to a capital punishment.

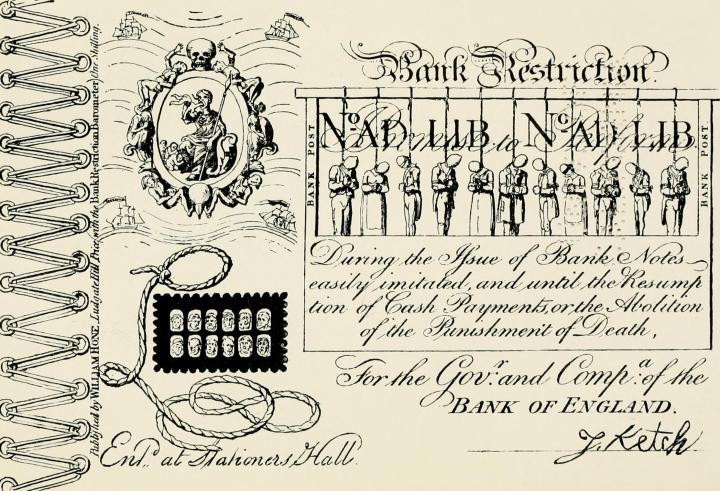

William Hone’s satirical banknote, signed by the hangman, Jack Ketch

Execution was a public ceremony outside the Debtor’s Door and the criminal who was about to be ‘launched into eternity’ was supposed to play their part to produce a meaningful lesson for the audience. In Charlotte’s case, this involved a solemn procession from her cell which started an agonising forty minutes before her execution. As Charlotte was being held in Newgate, she would have been privileged to have the Reverend Horace Cotton lead the line, along with the other condemned Mary Ann James (forgery), John Attel (forgery) and William Hatchman (robbery and burglary).

The newspapers reported that the ‘two women were respectability dressed in black, with white caps and frill’. They also scored highly as the newspapers reported that their sleep had been unsettled;that was acceptable, but not as convincing as a full confession of guilt. The two men had sleep well and had, according to the newspapers, a tolerably hearty breakfast; this did not bode too well for their souls.

This was an excellent start for the two women, and it would not have been the first ceremony they would have ‘enjoyed’. The Reverend Horace Salusbury Cotton was four years into his job as the Ordinary of Newgate, but he was already famous for his “ fire and brimstone” Condemned Sermon in which those about to die were confronted an open coffin. It was a public, ticketed event and part of the ritual of state justice. All four of the condemned would have gone through this, and their reaction would have been part of the judgement made about them.

Charlotte was a forger, not a murderer, so the level of contrition needed was moderate. As she saw the public hangman holding the rope, she fainted away a little and had to be held while the rope was put around her neck. This was still a reasonable performance- reluctance to be hanged in this case was regarded as contrition; fainting away was an acknowledgement of the punishment; struggling with the hangman would have been unacceptable as it would indicate either cowardice or a refusal to accept the justice of her execution. Weeping bitterly would have been acceptable, as long as it was not caused by self-pity. Charlotte did weep bitterly; but it was the right type of weeping. She needed two men to get here to the scaffold but she was being guided and supported, not dragged.

All four were prepared for death and were to be dropped at the same time. There were prayers and handshakes and no recriminations or cowardice. However she did not receive full marks for her efforts. She did ask the mercy of the almighty and confessed to her sins, but made the mistake of claiming that she had been induced into the crime by others- she knew the other two forgers on the scaffold- in order to be transported to Botany Bay and be reunited with her criminal husband.

By the Regency period, an efficient hanging was one of the public expectations. It seems that the rope slipped from the ear of all four victims and ended up under their chin, vastly increasing the agony. Hatchman particularly and one of the other three suffered great agonies as the rope did not break their necks when the platform dropped away. The crowd booed and hissed on two occasions, and some members of the audience fainted away. They would have been an intimidating audience-two women hanged at the same time was a novelty, and the crowd was huge.

The audience was reasonably respectable up to that point. Two week later, Horace Cotton presided over the execution of wife murderer David Evans. On the whole he died as well as Charlotte. Most of the respectable checklist was achieved; reconciliation with his 15-year-old son, three hours unsettled sleep; acknowledgment of his guilt; melancholia but with fervent prayers; some help needed to reach the scaffold and his appeal to save his soul. He did, however, claim that his wife Elizabeth had been unfaithful to him. You were meant to accept your guilt unconditionally, not search for mitigation. He also had to suffer an audience of London lighterman (bargemen) who had popped over after a nights work to jeer at the victim.

It was Horace Cotton himself he gave the single for the drop, with an appropriate Biblical reference. Evans died immediately; largely because of the outrage at the bungled execution of Newman and the rest by the same hangman earlier that month. Jack Ketch- the nickname for the public hangmen- had got his act together. Evans dangled for the legally stipulated hour and then his body was sent to St Bartholomew’s for dissection.

It did not always go so well. In 1818, the murderer Francis Losch ‘went hard’ into eternity. He stabbed his wife to death, disembowelling her when she refused to continue to work as a prostitute for him. He was truculent and unapologetic at the scaffold. His only regret was that he was being hanged and he refused to admit to his real motives, claiming his wife’s actions had made him jealous. He did not go meekly to the scaffold, requiring wine to quieten him and two people to forcibly point him in the right direction. He was insufficient penitent and resigned and did not accept the justice of his punishment.

After writing this, I found this excellent article by Naomi Clifford

http://www.naomiclifford.com/charlotte-newman-mary-ann-james/

My approach is slightly different, but Naomi provides excellent background research and a different perspective.

My Georgian and Victorian books

The Dark Days of Georgian Britain– a political and social history of the Regency. More details here

Passengers – a social history of Britain 1780-1840 told through travel, transport, roads and hospitality. More details here

Radical Victorians– nineteen radical Victorian men and women who dared to think differently. More details here

My new Georgian book Voices of the Georgian Age

Interested in the English Civil War? Try here

4 thoughts on “A Regency guide to your behaviour when being hanged; 1818”